In a world where shocks are no longer rare but routine, the cost of inaction is rising. Optimizing supply chains solely for efficiency may deliver short-term gains, but it leaves firms dangerously exposed to disruption. Resilience, while not free, offers long-term value through continuity, agility, and reputational strength.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution—but there is a method. By applying dynamic cost-benefit analysis, companies can tailor resilience strategies to their specific risk profiles and operational realities. The goal is not to abandon efficiency, but to recalibrate it for a world where preparedness is not a trade-off, but a competitive advantage.

Efficiency vs. resilience: A strategic trade-off

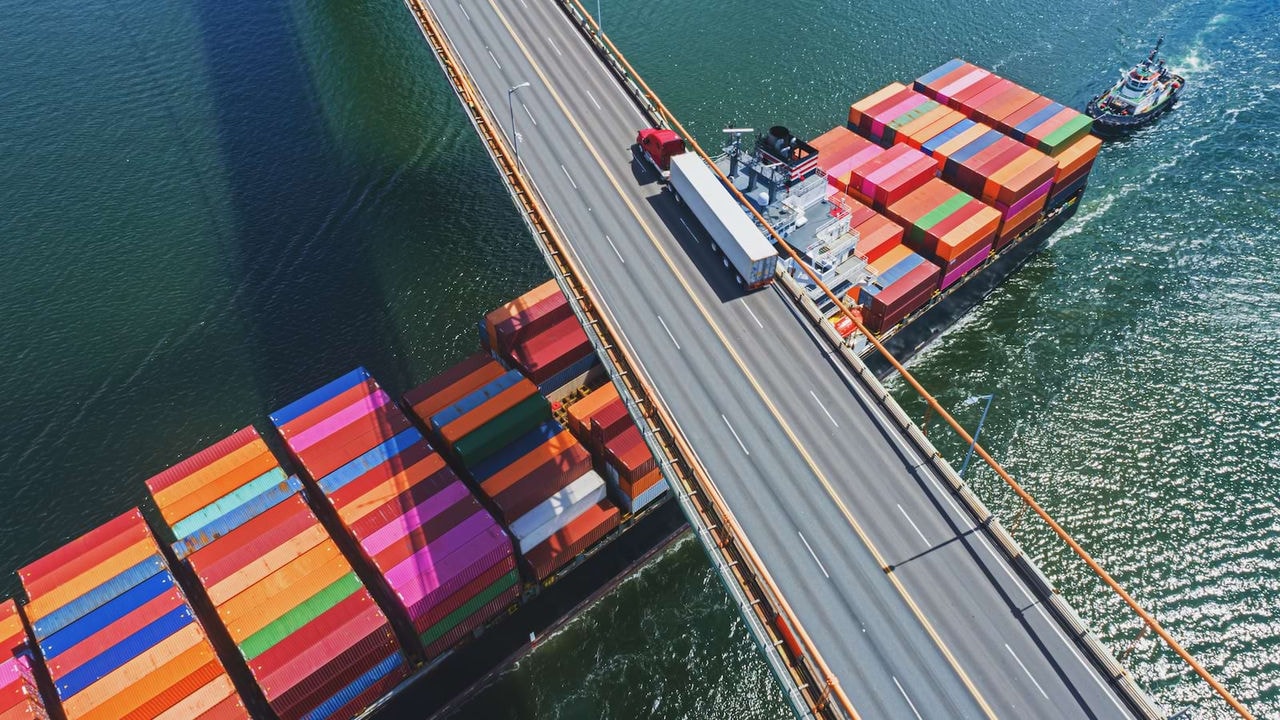

On a quiet Tuesday morning, a Dutch supermarket receives only half its usual fresh produce shipment. The issue isn’t scarcity at the source, but cascading logistical failures: a sick truck driver in Poland, a bottleneck at the German border due to new customs checks, and a delayed ship rerouted because of the Red Sea tensions. What used to be an exception is now routine.

It is a shift that mirrors a broader trend: resilience is no longer a nice-to-have, it’s becoming a strategic necessity - not only for firms managing supply chains, but for governments steering economies. The trade-off between resilience and efficiency is, at its heart, an economic decision. Hyper-efficient systems minimize cost by eliminating redundancy, diversity and buffers: just-in-time inventories, lean staffing, single-source suppliers. They thrive in stable times. But in volatile contexts, they become brittle.

A changed risk environment

The last five years brought a cascade of global shocks: a pandemic, war in Europe, rising geopolitical tensions. These events were not isolated - they compounded one another. And they exposed the fragility of systems optimized for stability. What’s new is that bad times are more frequent.

So the question becomes: do the benefits of efficiency outweigh the growing exposure to risk? Or is it time to trade some efficiency for more security? If the expected benefits of resilience - fewer disruptions, better continuity, greater agility - justify the cost, then resilience is the rational economic choice. In fact, IMF (2025) modelling finds that under plausible fragmentation risks, the welfare benefits of diversification outweigh its upfront costs.

With more risk, the value of resilience increases

Policy uncertainty has also spiked. PwC’s Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (2025) shows historically high levels of unpredictability in the Netherlands, reinforcing the case for resilience. Risk is no longer theoretical. It is a daily operational and policy reality. With more risk, the value of resilience increases. That’s true for shipping routes and energy supply, just as it is for government budgets and health systems.

This principle is well understood in other domains. Households buy insurance. Investors diversify portfolios. Governments deploy automatic stabilizers. These are all strategies that trade a bit of peak performance for better outcomes in bad times.

No one-size-fits-all strategy

Importantly, the trade-off looks different for each company, industry, and country. A semiconductor factory might grind to a halt for lack of a single part. A logistics firm may recover quickly with alternate routes. A small, open economy might prioritize energy autonomy; a large one may focus on financial stability.

There is no universal blueprint. But there is a shared logic: not every resilience strategy has to be expensive. Some interventions offer high returns at relatively low cost - such as improving supply chain visibility, building dual sourcing options, or enhancing scenario planning. These “cheap resilience” strategies can significantly improve shock absorption without major sacrifices in efficiency.

Prioritizing targeted, risk-adjusted investments

Research supports this. OECD data (2025) shows that sectors like electronics and pharmaceuticals rely heavily on foreign inputs, making targeted resilience policies – like dual sourcing or stockpiling - more effective than localization. Aldrighetti et al. (2021) further shows that the cost of resilience depends on network design, type of disruption and time to recovery - some investments are more beneficial than others.

The optimal resilience strategy may not be universal, but it can be economically optimized. Rather than pursuing broad-brush reshoring strategies—which often come with high costs and limited flexibility—firms and governments should prioritize targeted, risk-adjusted investments. These include dual or multi-sourcing for critical inputs, regional diversification of suppliers, strategic stockpiling of high-risk components, and investments in digital supply chain visibility. Such calibrated measures allow organizations to enhance resilience where it matters most, without undermining overall efficiency.

A practical framework: Making cost-benefit analysis actionable

To help companies navigate the trade-off between efficiency and resilience, we propose a four-step cost-benefit framework rooted in economic reasoning.

First, firms must define their strategic context. This means assessing their exposure to disruption-whether geopolitical, environmental, or operational-and identifying critical inputs or processes that could cause systemic failure if interrupted. Just as important is understanding how long a company can afford to be disrupted before facing serious commercial or reputational damage.

Second, organizations need to identify and quantify the costs of shifting from a Just-in-Time (JIT) to a Just-in-Case (JIC) approach. Resilience strategies-like buffer stocks, dual sourcing, or investing in backup capacity-often mean higher operational costs and capital lock-in. They can also introduce complexity, requiring more coordination and investment in systems and people. While JIT keeps costs low in stable times, it can become very expensive when things go wrong.

Third, the benefits of resilience must be weighed carefully. These include fewer disruptions, faster recovery, stronger customer satisfaction, and reputational advantages. Although harder to quantify, they can be decisive. Firms that maintain continuity in a crisis don’t just avoid losses-they often win market share.

Finally, companies should model these trade-offs dynamically. That means simulating disruption scenarios, assigning probabilities to different risks, and evaluating strategies over time. A resilience investment may not pay off immediately-but in a shock-prone world, its long-term value can far exceed its upfront cost.

This structured approach allows firms to move past one-size-fits-all answers and instead tailor resilience strategies to their specific context-balancing costs and benefits in a world of rising uncertainty.

Parallels in economic policy

The same thinking applies at the macro level. Just as firms hold inventory or diversify suppliers, governments can increase strategic reserves, loosen fiscal rules, or revise debt ceilings to enable countercyclical spending. Some have reshored critical production, such as vaccines or energy, accepting higher costs in exchange for security.

But again, a full pivot away from efficiency is not optimal. OECD simulations (2025) suggest that large-scale reshoring could cut global trade by 18% and reduce global GDP by over 5%. In many cases, volatility would increase rather than decrease.

Resilience isn’t about isolation. It’s about flexibility, foresight, and the ability to absorb shocks without collapsing. As the IMF (2025) shows, accounting for trade rigidities and transition frictions — such as supplier lock-ins or labor immobility — makes the case for resilience stronger. Diversification, in this context, isn’t just about avoiding losses. It’s about managing adjustment costs in a more shock-prone world.

A shared framework: Cost-benefit thinking under uncertainty

Economics doesn’t offer a universal solution, but it does offer a method: dynamic cost-benefit analysis in uncertain environments. A cost-benefit analysis becomes dynamic when it accounts for how costs, benefits, and probabilities evolve over time, incorporating feedback effects, learning, and shifting conditions rather than relying on fixed assumptions.

Whether designing a supply chain or a national economic strategy, the goal is the same - optimize for today’s risks, not yesterday’s assumptions. That means accepting that some risks are worth mitigating, while others may be tolerable. It means recognizing that trade-offs are unavoidable - but decisions still must be made.

Some resilience investments will pay off handsomely. Others may never be needed. But delaying action out of indecision only amplifies exposure. And in a world where uncertainty is no longer cyclical, but structural, the cost of waiting is rising.

References:

- PwC, 2025 – Decline in long-term strategies due to policy uncertainty

- OECD, 2025 – Supply Chain Resilience Review

- IMF, 2025 – Supply Chain Diversification and Resilience, WP/25/102

- Aldrighetti et al., 2021 – Costs of Resilience and Disruptions in Supply Chain Network Design Models

How can you ensure your organisation remains resilient in the face of unexpected crises?

About the authors

Barbara Baarsma

Chief economist, PwC Netherlands

Barbara is chief economist of PwC Netherlands and in this role she heads the economic office of PwC. Since 2009, she has been professor of Applied Economics at the University of Amsterdam. In addition, she holds various other societal positions.

Rolf Bos

Director Operations, PwC Netherlands