Renewable energy is one of the major steps to achieve decarbonisation targets (perhaps one of the best-known new energy dynamics). However, renewable power can be unpredictable, for example when clouds block the sun or the wind stops blowing, which makes these energy supplies and prices more volatile and harder for organisations to manage. VPPAs (virtual power purchase agreements) can potentially deliver large benefits to companies, however, this is only the case when commodity risk management, and accounting and valuation nuances are understood and assessed in combination.

Corporates are reducing their carbon footprint and often seek to use ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ electricity. There are several ways in which a company can demonstrate that it has ‘used’ sustainable electricity, which may be used in combination with each other:

- Purchase of renewable energy certificates (RECs) on a stand-alone basis in the market.

RECs are created for each megawatt hour of electricity that is generated from a renewable energy resource, and they can be purchased by a company in the market and then ‘used’ (that is, cancelled or retired) by the company to offset its energy usage from non-renewable sources.

In this case, a company does not directly purchase green electricity from the grid but instead buys green energy certificates from other companies that generate green electricity to offset its use of non-green electricity. - Physical power purchase agreements (PPAs) for green electricity.

The company takes the physical delivery of green electricity (that is, title) under the contract from a particular generation facility at some point after the generation process. This is often at the interconnecting point between the generation facility and the grid or transmission system. - Financial settlement of green electricity through a VPPA and purchase of RECs from a generator.

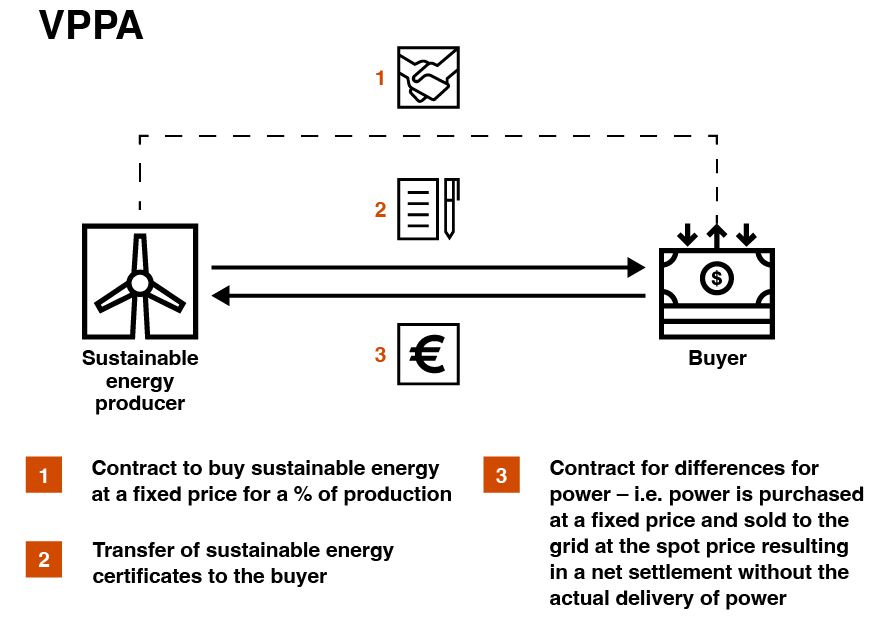

Unlike a PPA, this is not a contract for the purchase of electricity, but a long-term price agreement with a power plant, whereby RECs are also obtained. The power plant sells the electricity in the local market. VPPAs are sometimes called a ‘financial power purchase agreement’ or ‘contract for differences’ (CFD). In other words, power is settled for a fixed price and also sold directly by the generator for a variable price resulting in a net settlement to the purchaser of the VPPA without the actual delivery of the power next to the receipt of RECs. The RECs received can then be ‘used’ (that is, cancelled or retired) to offset actual energy usage from non-renewable sources.

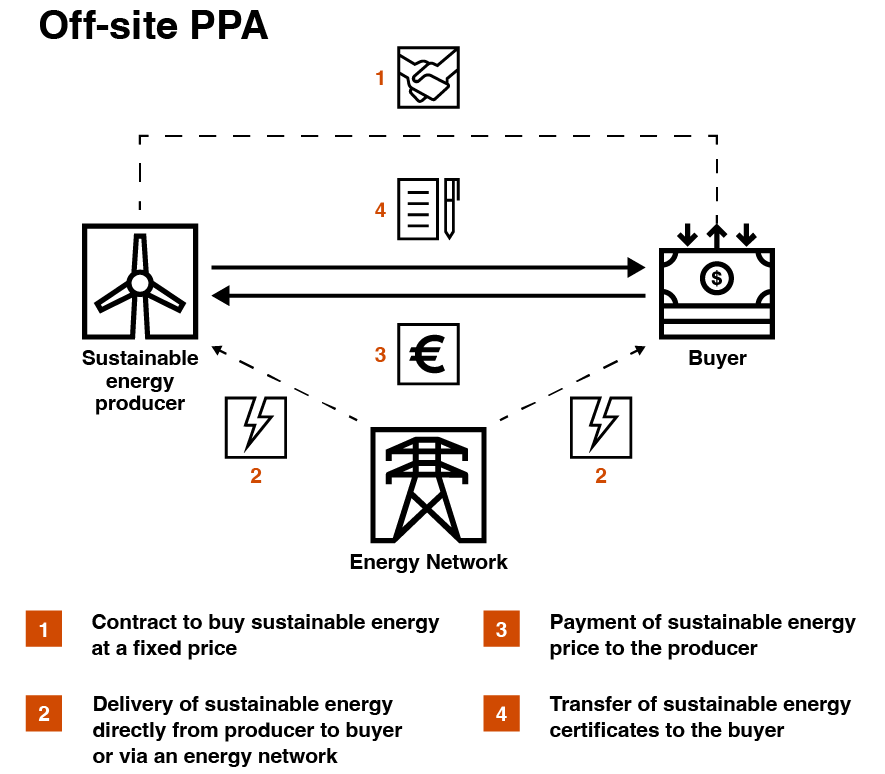

The difference between a PPA contract and a VPPA contract is illustrated using the figures below. As can be seen, a VPPA contract does not involve the physical delivery of energy through a power network to the recipient of the VPPA contract.

Climate strategy considerations

While entities typically follow all three ways of demonstrating the use of green energy mentioned above, VPPAs are becoming increasingly popular for meeting renewable energy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets, especially because there is no restriction on whether the off-taker is located on the same power grid as the renewable energy plant despite the need to consider multiple intersecting frameworks and standards in the reporting of GHG emissions reductions from the use of VPPAs.

Overall, VPPA arrangements are usually complex ways to meet renewable energy needs as there are also a number of accounting, valuation and risk management implications to consider.

Accounting considerations

From an accounting perspective, a company must first assess whether the contract is a PPA or a VPPA contract. Due to the unique nature of the electricity market and the lack of economic storage options, it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a contract relates to the PPA or a VPPA. It is essential to understand the nature of the agreement because the final accounting treatment often depends on it.

We will delve further into the VPPA contract in the remainder of this article.

Many VPPAs are ‘blended PPAs’, as the entity buys ‘physical’ renewable energy certificates (RECs) (that is, it obtains the actual certificates that it can resell or retire) and financially settles the ‘electricity’.

A VPPA contract must be assessed to determine whether the contract leads to consolidation (subsidiary), treatment as an associate, or as a joint venture. If this is not the case, it must be evaluated whether the contract leads to lease accounting.

In a standard VPPA contract where only RECs are purchased and paid for using the price differential between a fixed and floating price, these treatments as subsidiary, associate, joint venture or a lease are normally not applicable.

Host contract determination and embedded derivatives assessment

The host contract is for the purchase of a non-financial item: the RECs. Where the RECs are considered readily convertible to cash, or the host contract is otherwise net settleable, that host contract will need to be evaluated to determine if it qualifies for the ‘own use’ exemption under IFRS 9 ‘Financial Instruments’. To qualify for the own use exemption, a contract to buy or sell a non-financial item, in this case RECs, needs to be entered into and continue to be held to receive or deliver these RECs in accordance with the company’s expected purchase, sale or usage requirements.

Generally, if the RECs are being purchased by the company for cancellation, the host REC contract is likely to be an ‘own use’ contract under IFRS 9. On the other hand, if the company is engaging in trading of RECs (that is, it is purchasing RECs for resale on a short-term basis or otherwise net settling outstanding contracts in cash), the host REC contract will likely not qualify for ‘own use’ under IFRS 9, but as a derivative.

Once it has been determined that the host contract is not accounted for as a derivative (that is, it is not net settleable, or it is net settleable but qualifies for ‘own use’), the pricing formula for the purchase of RECs must be evaluated to determine if it contains embedded derivatives that require separation.

Some contracts outside the scope of IFRS 9 might contain price clauses that modify the contract’s cash flows. It is necessary to establish whether the underlying in a price adjustment feature is related or unrelated to the cost or fair value of the goods or services being sold or purchased in assessing the ‘closely related’ criterion.

In this case, although the company is only taking delivery of RECs, the pricing formula is based on the exposure to power prices while the company is not receiving electricity under the VPPA contract. A non-closely related embedded derivative, modelled as a floating-for-fixed electricity swap, is therefore bifurcated and measured at FVTPL (fair value through profit or loss).

The embedded derivative is not closely related; this is because, if a company were to purchase RECs separately from the electricity on a stand-alone basis, the gross exposure to electricity prices would not be present in that contract.

Valuation considerations

- The valuation of VPPAs is highly complex for many corporate buyers. Less sophisticated models may lack contract-specific factors (over-simplified), more complex models will often require third-party specialists.

- A lot of input parameters are unobservable (Level 3), but some unobservable inputs are based on historical data/long-term models (e.g. climate-related aspects), which are very stable. With that, observable input parameters (e.g. short end of power forward curve) are an important driver for value of VPPAs.

- The long-term nature and volume of VPPA contracts can lead to very significant fair value movements, which can far exceed the financial KPIs (e.g. 3x total EBIT) of a company, distorting the IFRS net profit line.

- Many IFRS reporters hesitate to enter into such contracts because of potential accounting implications.

Hedge accounting considerations

An embedded derivative that is separated from a contract might qualify as an eligible hedging instrument. Therefore, where the embedded electricity swap is separated from the ‘own use’ (or non-net settleable) host contract for RECs, the embedded derivative could potentially be designated in a cash flow hedging relationship. However, the usual sources of ineffectiveness might arise for such contracts, such as location/basis differences and timing differences.

In addition, only highly probable purchases of physical electricity can be designated as the hedged item. Therefore, if there is variability in the highly probable quantity of electricity purchased for operational needs, compared to what is required to be settled under the embedded derivative (which will vary, for example, based on wind production), ineffectiveness can arise. The unit of account for the ‘highly probable’ test needs to be carefully considered, and it should be reasonable in relation to the electricity pricing mechanism.

In some cases, sources of ineffectiveness might be so great that the hedge will not qualify for designation or will have to be de-designated. Economic relationships criteria for the application of hedge accounting should be carefully considered. For example, when the production facility of the seller of the VPPA is located in Norway while actual spot power purchases of the purchaser occur in the Netherlands, these prices may not have a sufficient economic relationship.

To the extent that the company designates the hybrid contract at FVTPL rather than separating the embedded derivative, or to the extent that the host contract for RECs does not meet the conditions for ‘own use’, hedge accounting (if achievable) will be more complex to apply, because the fair value of the hybrid contract measured at FVTPL will contain exposure to both power prices and REC prices.

Complexities in the application of hedge accounting for VPPAs

Risk management considerations

The general commodity risk management strategy should be aligned with the company’s risk management objective. For example, a company’s risk management strategy is currently to hedge commodities for two years and power prices are fixed in a VPPA arrangement for fifteen years. This way, the hedge designation of an embedded derivative separated from the VPPA contract, as a hedge of future power purchases over fifteen years, could be a sound economic hedge. However, it would not be aligned with the company’s risk management strategy to hedge no further than two years ahead and, therefore, would preclude the application of hedge accounting. This results in FVTPL accounting of the VPPA. This hedging risk management strategy to hedge two years ahead may exist because the company can adjust its retail prices for products every two years. Using the VPPA, the production costs related to the purchase of electricity is fixed for 15 years. This could create a problem as decreases in energy prices do not lead to lower production costs for the company, while competitors who did not fix the purchase prices can reduce their sale prices. This mismatch might create significant financial risk for the company. Therefore, the question whether the VPPA is a sound economic hedge should be considered from a holistic perspective. And if considered appropriate, the formal risk management strategy should be adjusted before hedge accounting is possible.

Another issue might exist if the company already has fixed purchase prices for the power consumption for the next two years. This company will not have exposure to the spot price of electricity for those years to use as a hedged item for the VPPA.

IASB future development

The IASB understands the complexities in regard to VPPA accounting when applying current standards. On 18 December 2024 the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issued amendments with changes to existing hedge accounting requirements. IFRS 9 currently requires the hedged item in a cash flow hedge to be ‘highly probable’ of occurring and thus mandates a designated fixed volume. The IASB is proposing requirements for when a renewable electricity contract is designated as the hedging instrument in a cash flow hedge of forecasted sales or purchases of electricity. Applying the amendments, an entity would be permitted to designate a variable nominal volume as the hedged item given certain criteria are met.

IASB has also amended the ‘own use’ criteria in IFRS 9. This part is particularly helpful for buyers in physical PPA contracts. The amendments have currently (per March 2025) not yet been adopted by the EU.

Conclusion

VPPA arrangements are becoming an increasingly popular way for companies to achieve their decarbonisation goals. Before they enter into a VPPA, companies should carefully consider the complexities involved. Collaboration between the procurement, sustainability, finance and treasury functions will be critical to understand VPPA arrangements and to determine the overall impact on organisations.