During COVID-19, supply chains in the apparel industry have proved to be unreliable and the demand for clothing fell dramatically. Together with overproduction this has led to a metaphorical ‘clothing mountain’. Resale of these clothes has not changed the system and reports of clothing destruction were not well received. On the other hand, an increasing number of Millennial and Gen Z consumers are selling their second-hand clothes online. Recommerce and sustainable fashion are very popular among young consumers and the industry picked up on this trend as an opportunity to accelerate the adoption of a more sustainable business model.

Amsterdam-based social enterprise Circle Economy promotes the practical and scalable implementation of the circular economy. One of the core projects of their textile programme is Switching Gear, which is supported by PwC. In this project, Circle Economy works with brands and retailers to help them design and launch rental and recommerce business model pilots.

Gwen Cunningham and Hélène Smits (co-leads of Switching Gear) and Switching Gear participants Jakob Dworsky (co-founder of Swedish online brand ASKET), Esther Oostdijk and Nancy Dingshoff (managing director and project manager at Dutch corporate wear company ETP), Annette Tenstam (strategy lead circularity and environmental sustainability at Swedish fashion company Lindex) and Zoé Daemen (sustainability manager at Dutch fashion brand Kuyichi) discuss trends and the adoption of recommerce and rental models in the fashion industry, together with PwC’s experts Jennifer Nelen and Amber Voets.

Credits: Circle Economy

Sustainability during the corona crisis

The Covid-19 pandemic has shaken up the fashion industry and forced fashion brands to refocus. When it comes to sustainability, including circularity, the reactions of market parties are twofold. Smits (Circle Economy): ‘We see that fashion brands who had not yet entered the path of circularity are now reluctant to do so because they have other priorities and fires to put out.’

Nelen (PwC): ‘These brands now primarily focus on cash management and liquidity for instance. However most fashion brands that have sustainability at the heart of their business model did not lose sight of the sustainability aspect during the corona crisis.’

Build resilience and become future-proof

Cunningham (Circle Economy): ‘Everyone is trying to weather the storm, but our partners tell us that they are now even more steadfast in their commitment to circularity because they see it as a way to build more resilience and become more future-proof.’

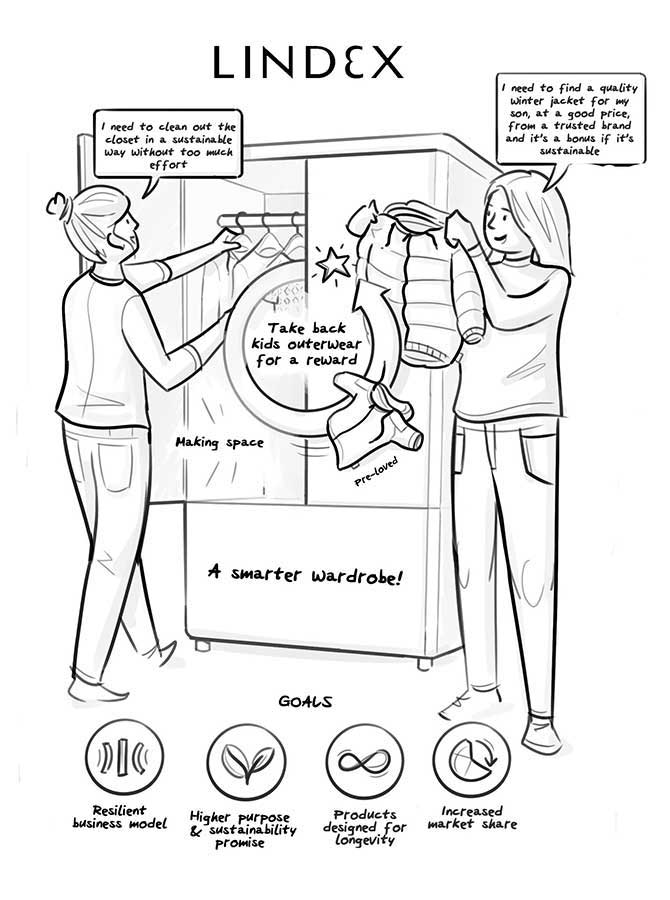

This is exactly how Lindex sees it. Tenstam: ‘As a company we are building resilience, for instance by focussing on circular business models and disconnecting business growth from product volume.’

Sustainable brands ASKET and Kuyichi were able to withstand the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the market because of their resilient and flexible business models without seasonal collections, sales or discounting. This means they could continue to supply their products from stock and were not left with unsold seasonal inventory.

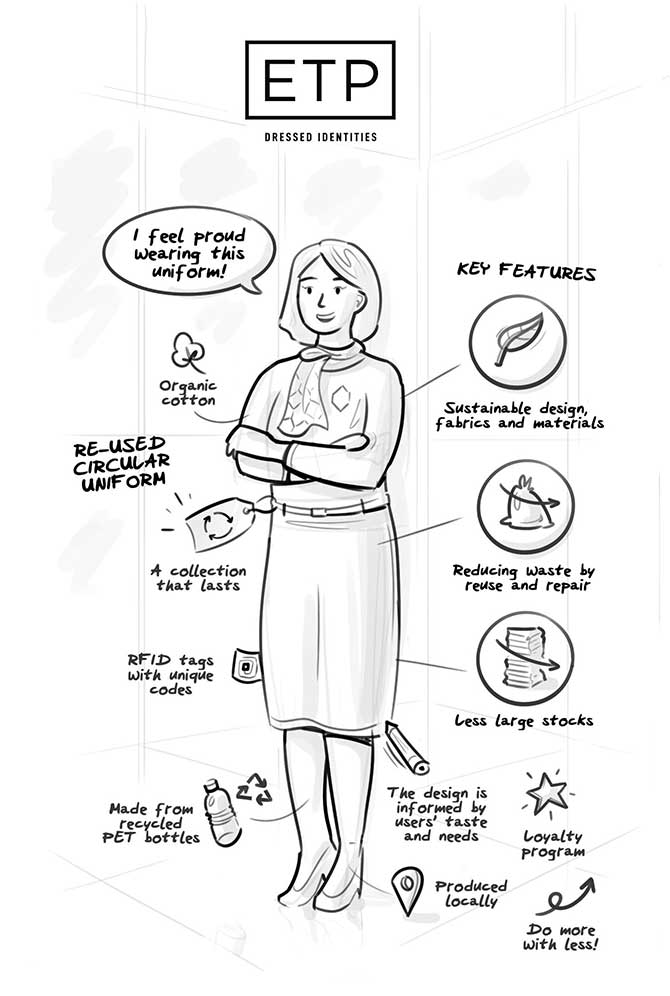

For corporate fashion company ETP the corona crisis meant more time to work on a new recommerce business model for taking back and redistributing or recycling used garments. Oostdijk (ETP): ‘Although our customers are very cost-conscious now, a lot of them are still willing to invest in joint initiatives to give a boost to sustainability and circularity.’

Recommerce solutions are increasing

Research shows that recommerce solutions will increase over the coming years. Nelen: ‘We see that our clients in the fashion industry are dealing with Corona-related supply chain challenges resulting in, for instance, excess inventory that is difficult to get rid of. Overstock can be sold on online marketplaces, donated or, which unfortunately often happens, thrown away.’

Cunningham: ‘The issue of waste became apparent during this whole crisis because the options to export waste to another country or get rid of it in other ways was difficult. In a way it has shown the cracks in the system we have seen for many years, but I think it became much more apparent than ever.’

Focus on the end-of-use phase of clothing

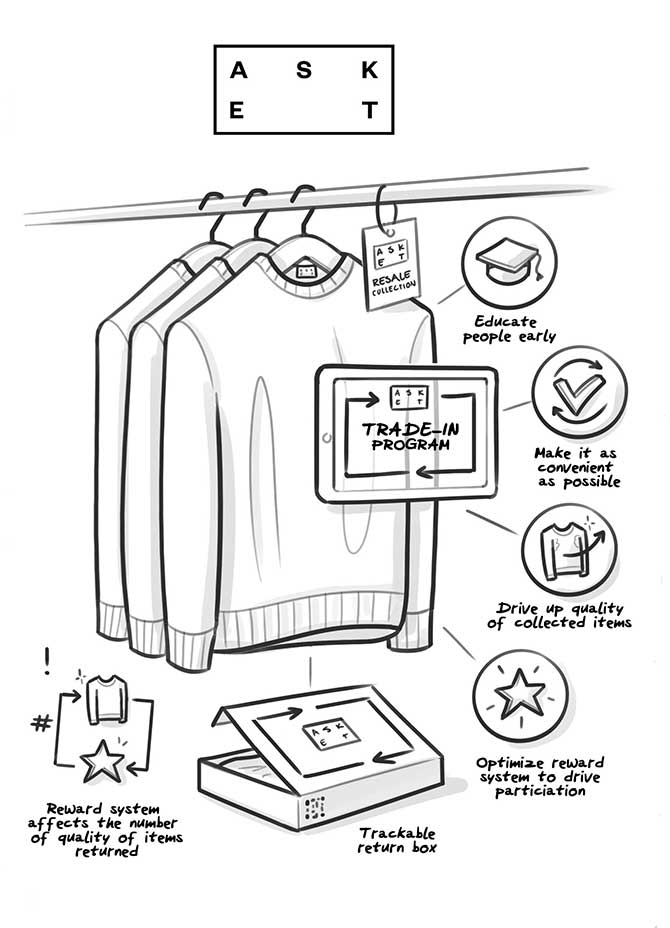

Circle Economy sees a shift in focus towards the end-of-use or end-of-life phase of textiles. The Switching Gear programme is trying to tap into, and facilitate, this trend. Cunningham: ‘Brands are realising more and more that they are responsible for the product beyond the point of sale. A few years ago, fashion brands only did the bare minimum in the sense that they sometimes had some sort of take-back scheme for worn clothes but did not actually handle that product or take control of it themselves. Now you see brands are more curious and want to know the quality of what is coming back in their system.’

For instance, Switching Gear participant ETP started a pilot at ABN Amro bank for their new reuse business model for corporate wear. Dingshoff: ‘In our reuse programme nothing can be thrown away, not even garments that show wear and tear. All unwanted garments are collected at the ABN Amro offices and then sorted and, if possible, made ready for our second-hand collection. We try to engage those who wear our clothes by telling the story behind reuse and recycling.’

Lindex also has a take-back programme. Tenstam: ‘In the majority of our stores we have a take-back programme in collaboration with partners that have high sustainability standards. As part of the Switching Gear project we are developing this further, aiming to create even greater value for both customer and brand.’

Credits: Circle Economy

Credits: Circle Economy

Incentives for recommerce en rental models

For consumers, the obvious incentives for recommerce and rental are a good price for the products and the desired sustainability effects. Daemen (Kuyichi): ‘Not buying and owning a garment should make you feel better, but the fact that you know the brand you bought is doing its best to be more sustainable.’

Dworsky (ASKET), ‘A lot of consumers don’t strive for ownership of all their clothes, think of party outfits and skiwear.’ Cunningham mentions ‘the thrill of the hunt’ as one of the biggest drivers for recommerce among the younger generations. ‘In my experience young people now are a bit exhausted by the mass market and are looking for something that is one of a kind and unique. Second-hand has the same scarcity factor as fashion drops of exclusive small collections.’

Take-back programmes and recommerce platforms

The benefits of recommerce and rental are different for consumers and fashion brands. Nelen mentions the fact that it’s very common to return unused garments to a department store in exchange for items of a different brand. ‘Similarly, in the future there will probably be an increasing number of (online) warehouses where consumers can return used garments for a voucher that can be used for another product in that warehouse.’

Smits: ‘It can be inconvenient for consumers if all fashion brands have their own take-back programme. But if you combine brands on a platform, consumers may lose the brand experience because they connect more with the platform. I see opportunities for such initiatives if the brands and consumers on the platform all share the same sustainability values.’

Integrating recommerce and rental models

Integrating recommerce and rental models requires business model restructuring as well as the technology to enable the new processes. Smits: ‘Rental is even more disruptive than recommerce as it requires a bigger change in existing operating systems than a recommerce model and therefore also requires more investments.

Nelen adds: ‘It also requires a mindshift among organisations as they need to move from offering a product to offering a service’. That’s why entering a partnership with an online rental platform can be a solution because it takes away some of that risk.’ Cunningham: ‘Unfortunately, we don’t have that many rental service providers in Europe, but I’m sure once there are more service providers, you’ll see a big bump in brand uptake.’

Creative consumers and recommerce

‘Now during the corona crisis, consumers buy less clothes and because they’re sitting at home a lot, they’re also more aware of unused items in their wardrobe,’ says Nelen. ‘More and more people are selling these items on online market platforms like Depop and Vinted.’ On Depop, it’s mainly Millennial and Gen Z consumers who sell second-hand clothing they refurbished themselves.

Nelen: ‘These consumers are the creators of the future. It’s almost as if they compete with commercial fashion brands in a way.’ Smits: ‘This trend is key in making a shift in the market, but the scalability of this specific business model of upcycling or making a design and customising it remains to be seen.’

Creative cooperation brands and innovators

There will be a lot of collaboration between brands and innovators, according to Circle Economy. Cunningham: ‘Now most common is what we call the incentivised resale via a third party. For instance, sustainable brand Reformation partnered with the resale innovator ThredUP - Reformation consumers could return their used clothing to ThredUp in exchange for store credit at sustainable fashion store Reformation.’

‘Another interesting example is Ralph Lauren that worked with a group of sellers from the online fashion marketplace Depop, to start curating a Ralph Lauren vintage collection which was then sold in a pop-up store. There are a lot of creative ways that these partnerships are going to grow.’

Kuyichi wants to set up a take-back programme for their garments, starting with denim wear, to give these a second life. Daemen: ‘We are looking for “repair” artists who know how to refurbish our denim into unique “new” items. As a pilot, we will work with Amsterdam-based artist Re-bell who can make patchwork unique items out of unsellable denims.’

Technology changed the appearance of second-hand

The appearance of second-hand fashion items has gone through a major transformation due to technology and professional merchandising, according to Circle Economy. Cunningham: ‘The stigma associated with second-hand has really been overcome by how professionally we can buy and resell second-hand clothes online now. On some platforms you need to double check if a garment is second-hand or not because it’s merchandised and described as if it’s a first-time product. That makes it more accessible and attractive to the average consumer.’

Credits: Circle Economy

Transparency through technology and data

Although not yet widely used in the circular fashion industry, emerging technology to make the journey of a garment more transparent, for instance through QR and RFID codes or NFC tags, is crucial in recommerce and rental models.

Dingshoff: ‘At ETP we started labelling our corporate wear with RFID chips, which makes it easy to register, identify and track our garments. This is important in the process of taking back garments from our customers for washing, repair or recycling.’

Scanning codes and tags on garments and shoes could also be interesting for consumers. Smits: ‘In this way, consumers could, for instance, check the age and original price of a garment and see for how much they can resell it.’

Voets (PwC): ‘A development related to that is blockchain. More and more fashion labels will use this technology to be able tell the story of the origin of their products.’

Generating data about garments

‘Technology and data analytics can help fashion brands forecast demand, which will then reduce overproduction and waste,’ says Nelen. Smits indicates that generating data about garments is also crucial in fashion recommerce and rental. Smits: ‘Take fashion rental, these companies really want to know more about the lifecycle of their products.’

Although they don’t have a business model for rental, ETP knows a lot about the use of their garments. Oostdijk: ‘At ETP we know exactly who wears our clothes, how often they wear it and when, and in what condition, these clothes are returned. Based on that knowledge we can, for instance, improve product designs and choose certain durable fabrics.’

Product performance and improvement

Cunningham: ‘Continually generating data on how a product performs and where certain products tend to have wear and tear or where issues arise, will hopefully result in better quality products over time. I can also imagine a subscription fashion service, such as Rent the Runway, would be interested to know how a certain product withstands use.’

Smits: ‘It’s interesting that most brands have quality controls before they sell a new product but lose sight of that after a product is sold. A positive example is the refurbished clothing programme of The North Face. Thanks to this programme they learn about possible weak spots in their products.’

Brands and the journey towards circularity

Nelen indicates that in order to become more sustainable, established organisations need to change the company’s internal ecosystem , including their culture, starting with changing their employee values and beliefs. ‘At the end of the day, these employees are also consumers who buy fashion. Bringing about real internal change is challenging and unfortunately some fashion brands don’t incorporate sustainability in their core as they don’t see immediate financial gains.’

Smits agrees and emphasises that circular business models should not be just a way to push more (new) product. ‘For some brands, incentivised returns and recommerce are a way to draw new customers in who then buy new garments in that same shop. Of course, it should work financially but the sustainability promise of circular business models is to reduce the need for new product.’

Large brands under public scrutiny

‘Existing fashion companies that want to become more sustainable need to change their behaviour that has remained unchanged for a long time,’ says Dworsky. ‘Especially if their business model is about selling large volumes faster and cheaper. And they have to do it in a real, meaningful and transparent way as they are under increased public scrutiny.’

Cunningham: ‘There is indeed a critical eye on big brands, but despite some historical backlash, big fashion brands are developing interesting initiatives. PVH recently announced the recommerce model Tommy for Life and sneaker start-up Allbirds collaborates with Adidas to design a sports shoe with the world’s lowest carbon footprint.’

Large brands can really make a change

‘If you look at the supply chain, bigger players have the power,’ says Smits. ‘If they decide to become more sustainable, they can really make a change because they have so much product volume. Besides, they are also funding or supporting a lot of innovations.’

Voets (PwC): ‘What I also see across the fashion industry is established fashion brands teaming up with start-ups.’ Established fashion brand Lindex is one of those brands. Tenstam: ‘In our transformation from a linear to a circular business model, we are looking to partner up with start-ups on a variety of topics, ranging from technology and software to logistics and product repair.’

Large brands need to be part of the journey to circularity. Smits: ‘Revenue from recommerce and rental could and should ultimately exceed revenue from the sale of new fashion. Hopefully, that’s where we are heading.’

Other trends reducing waste, CO2 emissions and water usage in the fashion industry

- Accelerating trend of 3D sampling: Dworsky: ‘At ASKET we use 3D models for our samples, which is faster as you don’t have to send samples back and forth and you use less material in the product development phase. This also means we could still move forward during the corona crisis even though factories were closed.’ ‘This technology can also be used as a demand management tool,’ Cunningham adds. ‘This means you can generate your product as a preview virtual product which you then only produce if it’s virtually sold.’ Jennifer Nelen has spoken extensively about this subject with digital fashion start-up The Fabricant

- Small timeless high-quality collections: Daemen (Kuyichi): ‘We need to produce less. A small high-quality collection needs to be the focus. If the lifecycle of fashion is too fast, you lose that focus.’ Dworsky (ASKET): ‘Our mission is to end fast consumption. By offering a permanent collection of high-quality essentials that last a long time we aim to contribute to reducing the consumption of clothes.’

- Recycled materials: ETP is testing the possibilities of recycled polyester fibre rPET for their blends and started a recycling pilot at ABN Amro. Oostdijk: ‘We take back used garments and recycle these to yarn, add some virgin material and then make new fabrics to be used in new corporate wear for ABN Amro.’ Dworsky: ‘At ASKET we use recycled cashmere and wool for instance. Although still in its initial stages, recycled cotton is also becoming more of an option, especially in denim wear.’ In one-third of Kuyichi’s denim wear, post-consumer recycled denim fibres are used. Daemen: ‘Now, we also want to include our own denim in that recycling stream, but of course only if the items are unwearable.’ Lindex has set the goal to use 100% recycled or sustainable materials by 2025. Tenstam: ‘We are using rPET, recycled polyamide from PIW, recycled wool, and most of our denims include recycled cotton.’

- Organic materials: Only about one per cent of all cotton production in the world is organic. Dworsky: ‘From a sustainability angle non-organic cotton is not a great material, so ASKET aims to fully switch to organic cotton in the coming year. Although some non-organic garments will still be in rotation, all new orders will be for organic.’ Lindex is one of the top ten users of organic cotton worldwide. Tenstam: ‘Today, 78 percent of our cotton is organic.’ Cotton has a link to the founding story of Kuyichi. Daemen: ‘The cotton industry is not sustainable and one of our founders, NGO Solidaridad, wanted to give a push to organic cotton production. Because fashion brands found organic cotton too expensive, Solidaridad created its own market by founding Kuyichi in 2001. At Kuyichi we’ve also processed innovative fibres and textiles, such as hemp and soy fibres, and thus propagate these innovations in the market.’